Why this inflation is different

Our viewpoint

26 April 2024

Inflation continues to dominate news headlines across economics, business and finance globally, even today, when signs of its abatement signal positive sentiment in some advanced countries. The actions of central banks have differed in terms of timing, direction (cuts or rises) and communication. Also, few central bank leaders have been criticised for their delayed actions and excessive cautiousness.

Why is inflation of consequence?

Inflation is important to understand for households as it affects the standard of living. Similarly, corporates need to understand that inflation affects the interest rates set by commercial banks which affect the cost of borrowing and the cost of capital; for investors inflation is key as it drives the wedge between nominal and real returns and having a better understanding of inflation dynamics can help investors achieve their real return targets. From a country viewpoint, it is important as it affects real GDP per capita and international competitiveness.

What do we mean by inflation and what drives it?

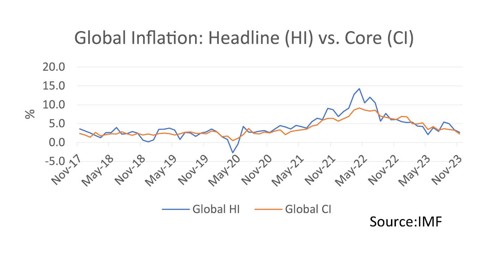

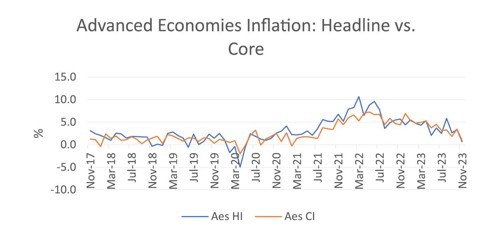

We summarise a few high-level lessons from experts (academic researchers and central bankers) regarding why this inflation has taken so long to tame, part of it is also which inflation measure to tame: “headline” or “core”. Headline inflation is the most popular measure of broad inflation based typically on the Consumer Price index (CPI). In the UK, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) uses Consumer Price Index including housing costs (CPIH) as the measure of headline inflation. Core Inflation focuses on the more persistent or durable part of consumer price inflation, expected to last into the medium or long term. It typically excludes food and fuel components of the CPI. During periods of high inflation volatility, there is greater interest in core inflation. The two measures have peaked at different times and are decreasing at different rates too (see charts below).

What has driven recent inflation and how have policy makers dealt with it?

Today's inflationary environment stems from a combination of different factors which make it challenging for economies to target inflationary control mechanisms. These include the following:

Multiple origins of current inflationary episode

The origins of this current inflation (see figure January 2024 IMF’s World Economic Outlook update) have been a global COVID shock (bigger globally than financial crises shocks since the 1950s) and a huge increase in energy prices like the oil shocks of the 1970s, followed by supply chain disruptions. The central banks and policy makers were hit by a global surprise—the current inflation episode was global and unanticipated (IMF inflation forecasts) even at the beginning of 2021. A 2024 CEPR research report (English, Forbes and Ubide) shows that supply shocks caused inflation spikes whereas demand shocks do not; inflation is relatively stable around demand shocks historically. Inflation picks up when the supply chain pressure index spikes up.

Energy shocks, very different than the 70's...so is today's consumer basket

The current episode featured a large broad-based energy shock which hit all commodities in the sector, unlike in the 1970s where the prices of electricity and natural gas did not go up. Electricity and natural gas prices factor directly into core inflation. Despite countries having similar inflation rates, the observed peak inflation rates have varied across countries ranging from Switzerland 2% to Sweden at 12%, France 6% to some of the Baltics at 20%. The composition of inflation too has differed across countries since 2019. Bernanke & Blanchard (2024) found that the main inflationary burst was caused differently across 11 economies by different major factors: Japan (food prices), US & UK (slack), Euro Zone (shortages).

Central bank responses have varied across regions and EM vs DM

Monetary policy strategies differed too: the level of inflation rates at which central banks first raised rates were also very different with Turkey (2020) core inflation at close to 12%, Brazil (early 2021) at core close to 2%, US (early 2022) with core close to 6%, Switzerland (end 2022) at 2% core. Emerging markets raised rates quicker than advanced economies as they were more exposed to global shocks and less confident about anchored stable inflationary expectations. Expansionary fiscal policy did help the central banks in terms of energy subsidies (open ended price caps) leading to reduced inflation as per IMF research.

Unprecedented geopolitical strains in post-war era

The current inflationary episode is against the backdrop of a recently very strained geopolitical ecosystem. Advanced country central banks were struggling to meet the inflation target of 2% over nearly two decades and suddenly inflation spiked causing them to deal with the question that divided experts — is this episode a temporary one or a more permanent one warranting serious immediate action? The policy response of central banks has been to tighten monetary policy by raising interest rates. Also, evidence shows that central banks were not “late” in acting.

Countries facing asymmetric energy shocks with different economic structures

While the COVID shock affected different countries similarly in terms of direction, the energy shocks were asymmetric between energy importers (euro area) versus energy exporters (the US). The euro area’s terms of trade deteriorated followed by lower consumption and aggregate investment relative to the US, thus explaining why the US demand recovery was so much quicker towards pre-pandemic levels. The composition structure of GDP based on the demand side is also very different in terms of the openness of the economies or the share of consumption expenditures in GDP. Therefore, the disinflationary process has a different speed across different economies due to different structural features and sectoral differences. The oil shocks are more persistent and are heterogeneous i.e., they do not affect all sectors of the economy similarly compared to demand shocks; the energy intensive sectors suffer more than those less energy dependent.

While central banks and policymakers have been criticised for their actions, based on two indicators that they measure their policy actions against, they have done fairly well. They have managed to:

- keep inflation expectations anchored and

- despite the large energy shock, inflation peaked at a much lower level and started declining much earlier compared to previous episodes.

Unemployment over 2021-24 in most major economies has trended downwards with less damage to labour markets and real wage growth. But there remain macro-financial risks (debt service ratios and house prices) if policy interest rates are high. Recent research has highlighted the role of the financial conditions index and nominal rigidities of wages and input costs in different countries in helping central bankers and policy makers understand the inflation dynamics better.

Conclusion and outlook

Inflation forecasting is hard and hitting inflation targets is not too easy in a complex world. The supply side and global vs. local components of inflation are important to understand and the policy rates have not been raised uniformly by different central banks. Services inflation, goods inflation and headline inflation have exhibited gaps across major advanced economies such as the UK, US and Eurozone. While goods and services inflation are decelerating towards historical norms their patterns have been different and need to be different for the conditional forecasts to be right.

The UK’s supply side has deviated and not recovered especially in terms of recovery towards labour participation rates and labour productivity relative to the US and Eurozone. The domestic demand and supply factors have played an important part in driving core inflation. The UK labour market's structural features are what keeps inflation higher as well as its reliance on global supplies for personal consumption expenditures. Examining micro data underlying financial conditions and global effects on inflation (as BOE has started doing) should provide better insights in tackling inflation.

I believe that monetary policy and central bankers cannot effectively address macro imbalances and inflation issues with their current toolkits (which contain blunt instruments and effects of their actions are unlikely to see fruit in the immediate or near term). Monetary policy transmission mechanisms are not the same as in the 1980s.1990s and noughties with debate and disagreement regarding them. I believe that a combination of fiscal policy, monetary policy and structural policy (recall the late Japanese PM Shinzo Abe’s 3-Arrows strategy for a deflationary structurally weak demand economy) are needed for effective macro policy effectiveness in a more complex world than policy orthodoxy has seen in the past. Ultimately, we are not yet out of the woods on inflation and there is all to play for, with different central banks facing different challenges even across EM and DM countries.